The Unpredictability of Mountain Climbing

Even when I really think hard about it, I can’t remember why I’ve always loved the idea of tall, snow-covered mountains, prayer flags, suffocating altitudes and the the desire to get on top of one of those mountains some day. The thought of mountaineering as an athletic pursuit was still only a movie premise, but still, as a kid, mountains impressed me and I knew I wanted to venture into them one day.

The idea of actually climbing a mountain, of summitting something truly dangerous, was foreign to me for some time and it wasn’t until I was in my mid-twenties that I considered that idea a possibility. I figured, if that were to come true, I’d need to live near the mountains somewhere and know others who climbed mountains and have lots and lots of gear. Problem was, I lived in Florida.

In my twenties, I had the opportunity to live in Nepal teaching English and other things for a few months and see the Himalaya, a childhood dream ever since seeing Vertical Limit, but not until I was in my early thirties did my good friend, Doug Jackson, mention to me that he too wanted to climb a real mountain. Our first was an easy decision, Mount Rainier in Washington, a classic mountain, referred to as a great entrance to Himalayan climbing. And in 2019, our dream started to become a reality.

Fast forward to July, 2022, after an epidemic in 2020, and a cancelled climbing season due to record heat waves in 2021, through much training and doubt if we’d have what it takes, we made our ways to Seattle, our second time in two years, to hopefully summit the 14,441ft high dormant volcano, Mount Rainier.

Arrival: Ashford and a Glimpse of Rainier

We arrived on a Saturday in traditional fashion, getting lost in SeaTac airport, picking up our moderately OK rental car, and heading off to our first destination, a little ‘by the wharf’ seafood joint, Chinook’s, our now traditional spot. I kept the seasonal beers to a minumum as I wanted to make sure I was as 100% as I could be for the start of our trip, which was still about 3-4 days away.

After lunch, visiting the flagship REI – and not buying really anything of value and then leaving – another now cemented tradition we headed off to a grocery store, buying anything from fresh fruit, oatmeal, peanut butter, protein shakes, ramen and plenty of water.

After last year’s stay, more than an hour from the park entrance, we knew we had to get something closer. Whittaker’s Bunkhouse, on the RMI campus was perfect. A mere walk to orientation and RMI made things easy and relaxing.

Me carrying my 59lb pack, a pack of 24 bottles of water (29lbs) plus another 5 or so pounds of groceries. Practice for the climb, I guess. (~93 lbs?)

The trip into Ashford took about 2 hours and we passed many depressing towns, similar to our experience last year. After a while though, closer to Ashford, there were plenty of quaint mountain towns that almost felt like mining refuges of old. Eatonville was one of those towns and we noted they were going to celebrating the 4th via a banner that hung across the road.

Once we arrived in Ashford, things started to really sink in. The RMI campus reminds me of Herrnhut with its bunkhouse a hundred feet away from the outdoor cafe/food spot, and the few other accommodations such as the rental building, ‘pro shop’ and offices. There is even plenty of German to be seen from signs “Aufwidersehen” and old relic ice axes, books and oxygen masks. The air is fresh, crisp and somehow only brings back the fondest of memories and thoughts.

The room we rented is smaller than we pictured, but still, cozy and 20 ft from a 24/7 available hot tub. Above our two twin beds hang framed posters from what looks like the 80s. Above my bed, an advert of the 84 team led by Lou Whittaker who guided the first American team up the north side (china) of Everest. Above Doug’s bed hangs a similar posted but of Dhaulagiri. We find it still hard to fathom that on the list of people a part of that climb up the north side of Everest, is Ed Viesturs, someone we have read so much about, someone who started his mountaineering career out by guiding at RMI, the guide service we have selected to lead us up Rainier.

Relaxing in our Bunkhouse room, getting inspiration while watching Meru on our makeshift iPad cinema station complete with Bluetooth speaker “surround sound”.

First Night at Rainier National Park

What about a different experience compared to last year. Our stay in Ashford provided a gratuitous amount of comforts last year never gave. But more than that, the mountain is a completely different one. Last years record heat wave melted most of the snow off of the lower part of the mountain, and even higher up in the alpine zone, glaciers felt shaved, crevices were opening and there was much rock and dirt to be seen.

After quickly unpacking and gearing up, we made a treacherous drive for 45 minutes, 10 minutes of which took to get to the park entrance and another 35 up the park’s winding road to Paradise. The drive got scary quick as the clouds were very low and we drove through probably 10ft of visibility for 25+ minutes. Thankfully, Doug was careful and we took it slow.

With about an hour of light left, we snagged a great parking spot, geared up and immediately noticed that the park entrance steps just next to the Visitors Center were masked by snow. The paved trails that lead into the park, eventually to turn into dirt paths, were completely covered. Only trees and snow could be seen.

We arrived at the park just before dusk and felt like the only souls on the lower part of the mountain. It was quiet, blissful and invigorating being on the mountain with only our headlamps leading the way. Doug famously snagged this shot of me on our way out.

Sunday, Day Two: Rest Day

Down Time in Ashford

I’m pulled back to Herrnhut again during the rest day we have Sunday. After a nice morning breakfast of a shitty but still welcomed croissant egg and ham sandwich, oatmeal and tea, we immediately tried out the hot tub for 20 minutes, listening to easy going jazz piano, sipping rum. After taking a shower, we both wanted to try our best at a nap to get the body battery charged as much as possible. The real effort starts in two days with our Mountaineering School which will most likely last until 5PM.

After waking up around 2PM (5PM Florida time), we had lunch at the market cafe spot, ordering last years favorite Salmon Burger and a Coke Zero.

After a later lunch and a temptation of a slice of their amazing Pizza – which I didn’t let take over me – we took a walk through the trails behind the RMI property. Last year we had just barely poked our heads back there, but this time we really took a nice walk going deeper into the woods than last year. What felt like a typical forest trail at first quickly turned into a Jurassic Park-esque nature walk. I even played the album from John Williams at one point because there was some kind of magic in the air.

Ashford things

The town that encompasses the Charminar is always busy with locals looking for deals on bangles, ornate clothing or other jewelry. Most of the ware sold here is aimed for women.

Sugar cane juice is an excellent refresher in the warm sun, even in the winter months. For 10 RS, you can get a handpressed glass of the sugary drink.

After our return, Herrnhut came back to me. There were countless days in Germany during my brief time as a missionary where, after a lecture around lunch time, we had tons of idle time to do whatever we wanted. So many of those days tested our patience, and even though we were amongst a new, beautiful – for me, ethereal – experience, we sometimes felt bored.

I think it was only natural. More than that, I think it was good for me and for us today at the foothills of Rainier National Park. Those times really challenge me to be present and accept “boredom”, whatever that means. Whether it’s simply being alone with my thoughts on a porch gazing off into cloud layered mountains in the background, or taking time considering the smell of the air, or how the light tends to appear different in the PNW.

Downtime is something I look forward to. It’s the thing that separates me from my everyday back in Orlando because I can’t rely on habits back home, clocking into the PlayStation or numbing my mind with the TV. I get to sit intimately with myself, my predicament and my surroundings. I get to drink it in intentionally and if I’m honest, that’s something that’s hard for me in everyday life. I’m a stress eater or at least, maybe that’s what they call it. I’m usually first to finish my food and the person someone says “did you get to enjoy your food at all” to.

Day Three: Orientation in Ashford

Finally the day had come where our mountain climbing trip actually began. This wasn’t our first attempt at climbing the mountain, or at least, it wasn’t our first time signing up, training and having hopes of getting to our first day of orientation.

More than three years ago, my friend Doug Jackson and I set out on a journey together to hopefully one day climb Mount Rainier. I‘d always wanted to climb mountains – become some type of a mountain climber – as a young kid, mountains were always fascinating to me. In the Himalaya, seeing prayer flags and seeing movies with Sherpa and Kathmandu, I felt a very far-away element to the whole thing that made me even more attracted to the concept. Not all mountains are remote beings, but many are, and most are without mercy but all with their own beauty, marvels of the tectonic evolution of our earth. I blame growing up, re-watching two key movies: Vertical Limit and Dante‘s Peak. Cheesy B-rated movies to some perhaps, but Vertical Limit had Ed Viesturs, the mountaineering vocabulary and many nuances that actually do exist in mountaineering.

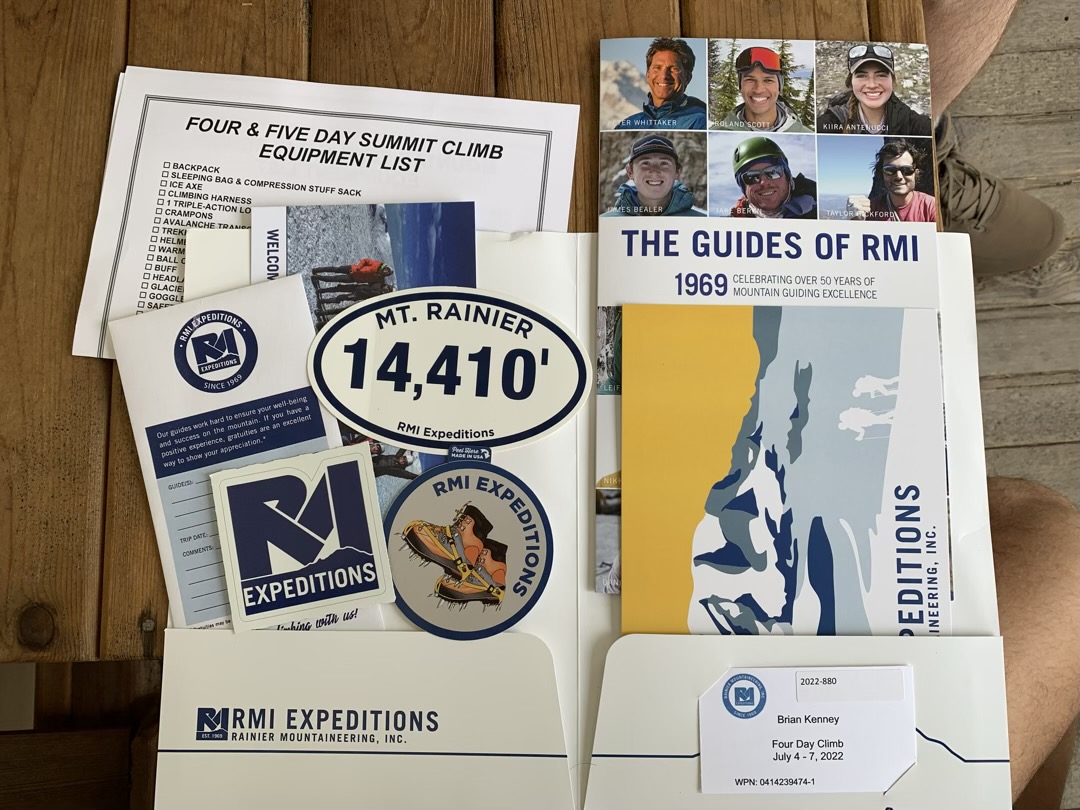

One day four or so years ago, Doug and I were walking to traditional taco Tuesday and without him really knowing I was interested, he brought up the dream of climbing Mount Rainier. Even more than that, he mentioned the only guiding company I had read about, RMI (Rainier Mountaineering International). We talked about it a great deal over tacos and committed to it. At first, I wasn’t sure if we could actually get to the door, if we‘d actually be able to save the money for the trip, if we’d get any amount of gear or be prepared enough to make it up the damn thing, but after the first year falling out due to Covid, and the second year* being cancelled due to a record heat wave closing the climbing season, we were at the door, and it was a dream that was coming true on the day of our orientation.

*On the second year, we arrived in Seattle, made it to Rainier National Park and had ourselves a few days of pre-trip bliss in the park, discovering the main trails that branch out from Paradise. On our second day, two days from our orientation, the beginning of our guided trip, we received a phone call from RMI while driving back from the park: the trip was being cancelled, possibly the entire mountain climbing season, as a record heat wave caused unclimbable conditions on Rainier. Crevasses were far too wide to be crossed and rock fall was all but a death sentence on the upper parts of the mountain. Doug and I, heart-broken and gutted, decided we weren’t going home. We found a tent for sale, got ourselves a permit to overnight up at Camp Muir and tried our best to at least get a taste for what was to come. We made it to Camp Muir at our own pace, falling in love with the process. We learned a lot on that trip, some good, some bad, but overall, we left that year more excited and more motivated for the next year’s season.

Our Lead Guide, Dustin Wittmier, who we learned a great deal from, shows us (using my gear) how to effectively pack all of our gear when setting off up the mountain.

Gear Shakedown: Dustin made sure we had all the necessary gear, clothing and equipment that, without, we would not able to make it up Rainier. Above is Doug and my gear.

Our team goes through their gear together.

Orientation day had us buzzing. It felt like the first day of college, or the excitement of arriving to a first date. To make the feeling ring even more true, RMI was set up like a campus, a large property complete with the RMI offices, Whittaker gear shop, the Rainier Bar and Grill, Whittaker Rental, Whittaker Bunkhouse (where Doug and I stayed), a cafe, and a few ‘mountain houses’ where slideshows or gatherings could be held.

After our presentation, we moved to a big grassy field where we threw down all of our gear and laid it out for inspection. Dustin, our lead guide for our trip talked about gear, types of gear and the importance of gear, following it up by going through every piece, having climbers hold up what was mentioned to ensure you had what you needed.

Seeing all of the gear – seeing all of my gear – had me salivating. I’ve always had a thing for gear and having the equipment to be a part of an activity. But I wanted to make sure I wasn’t someone who had all the gear and no experience. When I was living in Germany, towards the end of my time there, I had minimal gear and tons of experience. I was climbing almost daily and frankly, I didn’t have the money to get any more gear. So, while I had a lot of shit, and spent lots (lots) of money, I was so happy to finally be using that shit, and actually be a ‘member’ of the mountaineering club – a new member of course.

After the gear shake-down, Doug and I walked the mere 100 ft back to our bunk room and drooled over the next few days to come.

Waiting around for the guides on the morning of Mountaineering School. In the background is the Bar and Grill, the Guides Office and the Rental Store (to the right).

Day Four: Mountaineering School

Nearly each morning we woke up in Ashford, the day met us with sunny, cool weather. It was that refreshing feeling that’s perfectly balanced by the heat of the sun’s rays, but still cool enough outside to need a light hoodie if needed.

The night before, Doug and I packed our packs with all the required gear listed. It wasn’t everything we’d need for our actual climb but overall, it was close to it.

Our entire team met at the picnic tables on the RMI campus, threw our packs down and mingled with out teammates talking about what new sun hoodies we bought at the store or how excited we were to get started. I loved this moment. The guides let us know to meet at 8:00 AM but they wouldn’t get out of their guides meeting until 8:15, so there was this silent, suspenseful time to stand around and let the anticipation build up. It reminded me being a kid.

After a quick meeting talking about the agenda for the day, we threw our packs in the back of a sprinter van, hoped in and head out to Paradise, a 45 minute drive, with the majority of that being narrow switchbacks through the Rainier foothills and Forest. At Paradise, we got our packs out, used the bathroom, applied a generous amount of sunscreen to our faces and quickly set off at a brisk pace.

A good 15 minutes hike away, we found a nice flat section directly next to a steep incline. This would be our training spot for the next 4 plus hours.

Mountaineering School: Our group takes time to put on crampons.

The Rest Step

Our training began with a simple technique called the ‘Rest Step’, something we would use with virtually every step we took up and down the mountain. The rest step is a technique that allows climbers the ability to save energy as it involves resting on your back leg as you step forward with your front foot. Then, as your plant you lean with forward momentum and rest on that front leg for a brief moment as your back foot then becomes the front foot, stepping forward, repeating the process. It took a little getting used to at first and it definitely was never a second nature kind of thing, but over time, with lots of practice, it felt natural and easier to forget about.

Later in the day when we got our crampons on, things got even trickier since the stepping forward motion almost became a scuffing or kicking forward motion in order to gain purchase in the snow. The tricky part is, when you kick forward, you don’t want to catch your inside pant leg. It sounds easy, but crampons and boots are heavier than your average shoe and it does take some focus. I caught my pant leg once that day making a small puncture hole. After that, I was very alert to not do that again. Catching your pant legs or gaiters with a crampon spike is a common way of falling down a mountain.

Self-Arrest

After a few laps with our teams in line working on our rest step, we were instructed to put on our helmets and to get out our ice axes. Things were about to get a little more serious, or at least, what we were about to do implied the natural seriousness to what we were getting ourselves into.

Once we were all dressed for the next lesson, we split into smaller groups and headed up onto a steeper part of the hill. It was steep enough that if you were to sit on your butt, you’d slide down pretty quickly. Walking up the hill – using the rest step – was a lot more fun now but still a little challenging since we hadn’t put on Crampons yet.

Self-Arrest is one of the most important skills one can have for glacier or mountain travel. In essence, its the process of using an ice axe to arrest your fall, down a mountain. In detail, there is a lot of body movement and physics involved in self-arresting most efficiently. I figured it would be easier to show a video on how this looks, rather than explain it. We learned numerous ways of getting into self-arrest and tested those out on the mountain. It was exhausting and lots of snow got packed into our helmets and jacket collars.

Rope Travel

After a ‘mountain lunch’, we snapped on locking carabiners and circled around getting a speech on rope travel. Something that separates climbing to the top of Rainier from a typical day hike in Rainier National Park, is the technical pieces that are needed to stay safe and get you beyond certain parts of the mountain.

One of the biggest dangers during glacier travel are crevasses. Being roped up is one of the biggest ways to mitigate the danger of dying at the bottom of a crevasse, which could be hundreds of feet below. In essence, climbers are all secured to a dry rope in intervals of about 30, depending on the size of the rope party, using a figure-8 or butterfly style knot. The idea is, if one person falls on the mountain, the other climbers become saving anchors that arrest and stop the falling climber from truly falling.

Roping up, walking with an ice axe takes a lot of focus. Now, with those added techniques, along with the rest step, it was easy for the brain to get a little overwhelmed, making sure the rope was on one side of you, the ice axe was on the other, and that the rope tension was just right. A rope that’s too tight between climbers can cause someone to be pulled or not have room enough to maneuver, but a rope that has too much slack can be a big problem is someone fell because that slack would tighten and the force of that tightening would catapult one or all attached climbers. So paying serious attention was very important. Like I said, things being evidently serious.

Doug and I would catch each other looking wide eyed at each other as to say “Holy shit, we aren’t playing around anymore.”

This element of seriousness made the whole experience that much more valuable to me. I wasn’t intimidated, but rather validated that this journey into mountaineering was maybe right for me. I find it an element of human nature – one that we definitely fight against in our comforting worlds – to demand a primitive element that engages moments of focus brought on by grave or life threatening danger and to combat that with a mastery of self. I don’t see this like someone might see an adrenaline seeking person. Yes, there are moments of adrenaline in mountain climbing, but the majority of the experience requires a calmness, a centering of breathe and an intense focus on body awareness. Climbers need to be able to make calculated decisions at any given moment. Adrenaline does not cater to these needs.

Wednesday, Day Five: Climb to Camp Muir

I’ve never been very good at getting sleep the night before Christmas, or any other non-typical event in life. And while I didn’t get the best sleep of my life, I had been pretty worn out from the previous day’s hikes. So, waking up the morning of the climb, I felt almost 100% excitement for the unknown ahead of me. A slight anxiety loomed in the smallest corner of my mind of only one question really: was I fit enough to make it to the top?

It was starting to feel like a summer camp, everyone meeting at the RMI base camp, setting down their packs, finding their small little friend group, waiting on the guides to emerge from their morning meeting. Doug and I showed and killed time talking to the other climbers and if I’m honest, had a little fun guessing who would make it and who might not. At this point, I was confident in myself and if conditions were average or better, I couldn’t think of anything that would prevent me from toughing it out. We also knew deep down that anyone on our trip had the ability. Mountain climbing is not typically a sport where obvious muscle and build stands out. If anything, most of mountaineering is a hidden fitness, a fitness of the heart and the mind.

Before the guests arrive, Rishi and close family pose for a few photos before the sunlight fades away.

Before the guests arrive, Rishi and close family pose for a few photos before the sunlight fades away.

As we huddled around, we started asking one other if we could put on the other’s pack to test the weight. Someone mentioned there was a scale in the rental store, so we all ran over to see who was going to be suffering the most. A few packs weighed in at 31lbs, Doug was at 34lbs and I, without much shock or surprise, weighed in at 39lbs. I won, and I would be hauling the heaviest pack – with exception to the guides who were responsible for hauling all of the protection and necessary gear up with us. This included snow pickets, rope, two hot water carafes and supplies that might have been needed for resupply at Camp Muir. I thought about what I could have not brought or how I might have spared a few pounds. Ultimately, I made a deal with my mind that it would need to pull it’s own weight, because I wasn’t going to give in.

We set off for Paradise knowing we wouldn’t be back until the next day. On the bus, we all sat chatting, wearing masks (covid), with our boots next to us. It was nice sitting directly behind the guides overhearing past trips and stories of what its like being a guide. I felt like while I wish I could rewind my life 10 years and alter my course in life to be able to spend so much of my life’s time in the mountains, fit, and guiding others, I knew I still had plenty of time in life to invest in becoming a better mountaineer. I was just happy to finally be on the bus heading to my first ‘expedition’.

We pulled our gaiter-integrated, high altitude boots on as we pulled into the parking lot at Paradise, a famous starting point for many of the trails at Rainier, including the trek to Camp Muir. Outside, a hundred or more tourists crowded the area before the trailhead begins, where last year it was clear to make out the iconic steps engraved with a quote from Join Muir, “…the most luxuriant and the most extravagantly beautiful of all of the alpine gardens I ever beheld in all my mountain-top wandering.”

Overall, the reception goes down in my book as one of the most surreal and enjoyable days of my life. A combination of the unexpected and the ancient, other-worldly location made for a memory that will be something I remember for the rest of my life. The fact that I was able to see it all unravel from outside looking in, dipping my toes in from time to time, allowed me time to observe and use my senses in a very transparent way.

The Climb Begins

Our guides instructed us to use the restroom, put on sunscreen and be ready to head off. This began the climb. It was at that moment when a scheduled breaks stepped in that the climb was ‘a-foot’. And with that, we set off, into a sand-like, slushy snow that caused you to slip and slide as you made pace with the guides. Last year, the snow didn’t start until we made it all the way to the Muir Snowfield which is at least an hour hike. It’s a big deal because it takes a lot more effort to stabilize yourself and gain ground in soft snow. If the snow is firm, it’s not as much of a problem.

We followed behind in single file, trying to stay a foot step width away from the person in front of us. The weight of my pack wasn’t very noticeable – that never seems to be an issue. I think the pace felt for many quite quick. I needed to go into focus mode after 20 or 30 minutes and I tried my best to keep my mind off of my heart rate. I thought there was no way I was steady in Zone 2, for me which is around 112bpm – 130bpm and probably hovering in lower Zone 3, but I had no way of solving that but by using the rest step and trying to breath as calmly as possible.

A place where much time took place during the first few days of the wedding was this living room. While it was common to not see a lot of furniture inside homes, space was always being used.

Couldn’t Stand the Weather

After a few breaks, we made it to the Muir Snowfield, where things get steeper, but thankfully, the snow is a little less soft. It wasn’t very long until the clouds started to make their presence known and the weather started to look a little worrying. Our guides let us know because of the potential for rain and even worse weather, we would pick up the pace a little. This came to many of us as a surprise as we already thought the pace was quite quick. At one point, Erin, who lives in Seattle and has the luxury of training at some type of altitude in the mountains, asked me what I do for work. I knew immediately two things: one, my answer would be brief and I would not have much more to say and two, Erin was going to make it to the top.

All of my mind was focused on staying in line, breathing and keeping my heart rate down. I was hovering at 150bpm which is where my Zone 4 starts. You don’t want to climb a mountain at Zone 4. This is the thing that destroys your energy as your body begins to function in an anaerobic state, building up lactic acid. When I saw that, I just summed it up to my watch not knowing my true heart rate or, that my Zone 4 must be higher since I was – although somewhat feeling it – doing quite fine.

Our break in a ping pong ball. This a common view when ascending to Camp Muir or Rainier in general. When clouds roll in, it happens quick and if the weather begin it is rain, you need to get hard shells on quick. What you don’t see here is our sweat soaked bodies from a speedy pace.

We took a break in a cloud. Climbing in a cloud on a overcast day is like living inside of a ping pong ball. You only see white, and have no way to orient yourself on the mountain. Climbing up or down a mountain in conditions like these without a guide or a GPS is suicide. Many hikers get lost or step into crevasses this way and are never seen again. During our break, it started to rain. We were already soaking in sweat from setting a blazing trail up the snowfield. Now we through our hard shell pants and jackets on, insulating a layer of sweat in between. I took my light gloves off to drink water, eat and fuck around with my pack. We cut out break short, usually 15 minutes, to 10 and stormed up the mountain trying to make it to Muir within the next hour. My hands were numb and my body was wet but mostly warm. I tried to warm my hands but just really did my best to mentally block everything out. I knew after some time, they would warm back up, and after 10 minutes past, they did.

This stretch of our hike to Muir destroyed me. My hear rate peaked at 181 which is insane, and freaked me out some. I had all kinds of doubts, anxiety and fear come over me. Last year, Doug and I had the luxury of being able to take it easy going up to Muir, still making decent time at six hours even with generous breaks, one spanning an hour drawing/listening to the Interstellar soundtrack. This year, I was nervous I would even make it to Camp Muir! I blamed myself. I wasn’t disciplined enough or hadn’t trained enough, even though I knew I had made a pretty damn good attempt, averaging around 11 hours a week, much of that cardio training. I had just gotten over Covid 3 weeks before the climb, Doug, 2 weeks. Our stamina was zapped and the conditions and pace were not helping.

I toughed it out because I knew I could. But when we got to the hut at Camp Muir, I was redlined. Even after an hour of laying down in our top-bunk, eating and drinking, I couldn’t get my heart rate below 100. Doug and I perched up in the top-corner of the available space in the RMI hut, which houses 3 sturdy wooden bunk platforms, allowing up to 19 people to sleep.

There was so much gear around us, lots of sweat, food wrappers and all we wanted was to shut off for a few hours and thankfully, we had a decent amount of time to “get horizontal” as our guides kept saying. They mentioned that while we might not be getting much sleep, the rest we could get would be from just laying down and being calm. We weren’t even sure if tomorrow would happen considering the winds and weather was not looking too great – another disappointing factor. The weeks before (and later we observed, after) were filled with perfect, calm weather. Our trip was still hopeful at best if not in danger of being stopped before we even got onto the Cowlitz Glacier, where Doug and myself slept last year. But that wasn’t in our power, so we rested and ate a freeze dried meal (like mountaineering tourists) and over time, things eased up.

Since it was a hassle to put on boots and climb down from the 3rd level bunk, we tried to either stay up top or stay outside dressed in our big heavy Himali Parkas which kept us warm in the brisk, cutting wind.

Dustin called a team meeting and laid out the next hours until Summit morning.

“Get something to eat if you haven’t. There’s plenty of warm water for tea or food. After that, try your best to get horizontal and rest. You probably won’t sleep much but as long as you rest, you will be OK.” He pointed to the window outside, “The weather doesn’t look amazing at the moment and we are monitoring the forecast. We are still hopeful but time will tell. I’ll be coming in at 12:30AM to wake everyone up. I’ll come in, turn on the light above me and set a 45 minute timer. You will need to eat, pack, use the restroom and do anything else you need and be outside ready within that time.”

We rested and walked outside for sunset to snag a few pictures and to use the bathroom one final time before zipping ourselves into our mummy-shaped sleeping bags. In retrospect, it’s amazing that sheer exhaustion didn’t have me asleep within minutes, but the wind outside, the adrenaline and anticipation of what was to come in a few hours and the fact that we were sleeping in a totally different environment made it difficult.

A very exhausted, but happy to be drinking hot chocolate Doug and Brian. Holly was nice enough to get this unflattering photos of us crammed into our corner of a version of paradise. Above Doug is a window that gave us crazy views of the weather rolling in.

The two lead guides of our trip. Dustin Wittmier in red was the leader of my group, group a. In the teal jacket, Josh McDowell, tells everyone his story of when he was a guide on Mount Everest, nearly losing his life.

Standing on the ridge line at Camp Muir, you see from left to right, the RMI hut, another guide hut in the middle and the ranger’s hut on the right. A cloud covers the Camp Muir making the photo appear almost black and white.

From the opposite side of the RMI hut looking out down the Muir Snowfield, the sun sets highlighting the various blues in the sky and distant Cascade mountains. Juxtaposed to the photo on the left, this photo was taken only an hour or two after.

Summit Morning

Heading Out onto the Cowlitz Glacier

I woke up abruptly in a warm sweat to a light turning on, hushed commotion and Dustin speaking in a quiet tone, “Weather looks good. Things could change, but right now, we are ready to go. You all have 45 minutes to get food, use the bathroom, pack and get outside”

45 minutes all of a sudden felt like 5 minutes. I scrambled to find and put in my contacts and get out my breakfast, a freeze dried package of berry granola and rice milk. It was chaos in the hut with everyone walking around, putting on boots or clothes, adding hot water to their food bags, maneuvering packs through a sea of people.

Doug mentioned to me that he and I were on a rope team alone with one of our guides, Augi. It felt a little like destiny. For a little over three years, we had been dreaming of this day, training together and planning this trip hoping we would finally get to the starting line. It was more of a symbol to me than anything. You can’t be social on a rope team with the focus required and the distance between climbers. But we would get to talk during breaks, and even then, we hardly had words or energy to waste.

Early morning rituals include Rishi and his family taking turns anointing one another with Kumkuma powder. Here, his sister places a small mark on his forehead, while his mother and father sit at his side.

Early morning rituals include Rishi and his family taking turns anointing one another with Kumkuma powder. Here, his sister places a small mark on his forehead, while his mother and father sit at his side.

Outside of the hut, we strapped on our crampons, fastened our helmets and made sure our headlamps were on. It was dark, quiet, but you could feel the mountain aching and breathing beneath and all around you.

Augi gave us clear instructions, most of which we were taught two days prior during our mountaineering, however he did tell us to peek up hill from time to time when traversing the Cowlitz Glacier. The Cowlitz Glacier is the glacier Doug and I spent the night on last year, and really the most of the after-Muir climb I was familiar with. The Cowlitz is a relatively gentle traverse over to Cathedral Gap, eventually onto the Ingraham Glacier. It looks like a 500 yd par 5 across the Cowlitz, but on a rope team, walking slowly using the rest step, it takes about 45 minutes to traverse. Augi told us to peek the slope from time to time because there is occasional rock fall crossing over the path to Cathedral Gap.

On a Mountain, donning battle gear (ice axe, crampons, helmet, harness attached to a rope), time is hard to keep track of. What felt like a million years was 45 minutes. We made it to mouth of Cathedral Gap, which slopes hard upwards. Taking a long switchback up, we cleared the Gap and, even though we couldn’t see much of anything in the dark, found ourselves on the Ingraham Glacier.

After a healthy 30-40 minutes as we slowed down as the group ahead of us paused, monitoring for rock fall and ice fall, I got Doug’s attention, “Bro, take a look behind us.”

A string of lights illuminated a linear path; the remaining rope teams traversing the Cowlitz glacier. Looking back for a mere few seconds helped us comprehend the scale of the glacier we were crossing. The lights were mere dots, strewn what looked to be 100+ meters in length. As we pressed on, I noticed the silence, the breathing of the mountain and the rhythmic kicking of crampons in firm, packed snow. It was one of the most beautiful combinations I’ve heard before.

I don’t remember when we took our first break, probably an hour or hour and fifteen minutes in, but I do remember feeling stronger during that push than any part of the climb, especiallystronger than our sludge up to Muir on the 6th. At our first break, I felt positive and was still pumping with adrenaline knowing we were really out there, in the dark, headlamps leading our way (really it was Augi’s amazing leadership).

Rope travel got easier and being in the back was nice and easy. I felt for Doug who seemed to struggle with footing and navigating the rope around switchbacks. Ideally, you want to keep the rope on the downhill side of the you which keeps it from getting in front of you.

Rishi poses for photos with family before being sent off to the wedding complex.

Rishi poses for photos with family before being sent off to the wedding complex.

Rishi poses for photos with family before being sent off to the wedding complex.

First Break and Ladder Crossing – near 11,200 ft

We trudged on and as the sun began to touch the cloud blanket, below us, I figured I was probably in the 135-145 bpm range. I covered my garmin up with my fleece sleeve purposefully so I wasn’t distracting myself, causing more anxiety during a time I needed to be focused. It could have been lower but, I felt good. We arrived at our first break, the morning light glowing off the slope, Little Tahoma below us, a spire like a sharp pyramid crowning the clouds behind it. Things were going so well at this point, but to be honest, we only tackled the easiest of the route, known as the Ingraham Direct. Things were about to get more steep, and thanks to the weather, a lot more intense overall.

A few hundred feet out from Ingraham Flats were the only two ladder crossings of the route. While most would imagine a ladder crossing at altitude being something most daunting, most terrifying, it was more fun and interesting than anything. The first crossing was a small ladder (horizontal) with wooden planks set for footing. This one was to cover a small crevasse that, while it looked gentle, was covered by a masked snow covering and was 3 feet wide. You wouldn’t want to test if the snow covering underneath to see if it fell through to a 100 ft grave. The second ladder crossing was much more real. It crossed a very wide crevasse this time. And I wasn’t as intimidated as I thought I would be stepping up to the cold aluminum ladder, tied into the earth by rope, slings and ice pickets. Maybe I’ve watched enough videos to visualize it and take away the shock and awe sensation. It was honestly fascinating to see into the earth and granted, below the glacier was the earth, and this glacier was really a 500ft tall or so piece of slowly moving ice, splitting like crème brûlée on top of the earth, most of my energy went into the focus I needed.

As we approached the ladder, excitement grew and I centered myself in the mountain and in the moment. My eyes widened and colors became rich and piercing to my eyes. I felt like a cheetah preparing to attack, pupils dilated , mind and body focused. I watched Augi turn back to us.

“Hey guys, we are going to climb up this ladder. I want you both to take it slow, one step at a time. Be intentional with your steps. Take your trekking pole and place it behind your back, between your back and pack so that it stays put in between your straps when you climb the ladder. Take your ice axe in your left hand and hold it, pick facing down. You will need it after the ladder where the slope is almost vertical for a moment. On the right, above the ladder is a guide rope for you to grab and use.”

I watched Augi demonstrate, blood and heart pumping, but slowing down as we were able to stand still. I wasn’t intimidated. If anything, I couldn’t wait for my turn. It felt like I finally got to take part in one of those traditional aspects of mountain climbing. Something where I could look back and say, “Yes, I did climb a ladder over a crevasse. No, climbing up Rainier is not just a hike.”

Next, Doug took the ladder and eased his way up, rung by rung. I had to pay attention here as part of your role in a rope team is to make sure the rope tension between people stays moderately taught. Too much slack and a fall could result in the next person or all people being snapped forward or back when the rope finally goes tight. So, as Doug inched his way up the ladder, I inched my way forward, towards the ladder, making sure the orange rope ahead of me was mostly tight, with a slight slack to make sure Doug had room to move.

One of my favorite images of the wedding: Rishi absolutely surrounded by photographers, family and walking under ribbons of handmade flower garlands. There was a sense of majesty felt, and the structures that were used to decorate the scenes and locations were almost always colorful, or golden.

Once Doug crossed, I stepped up to the first rung. This was the best thing ever. I was beyond thrilled. Even as I write this now, it’s hard to think through the excitement of re-visiting that memory. I wish I could have saved it like Dumbledore’s Pensieve. I was the main role in all of the mountain climbing movies I watched when I was younger. It was now my turn.

The ladder was angled at about a 75 degree angle and is actually two ladders roped – very tightly – together. I I reached forward with my right hand and grabbed a rung. Next, I placed my right foot on the lowest rung, carefully positioning my crampons so that the rung was directly in the middle of my foot. Next my left hand, which help my ice axe, took the rung above my right hand. I grabbed with a few fingers. Next my left foot stepped a rung above my right foot. While the ladder was very well installed into either side of the crevasse, and while I was sure it would be safe – this part of the climb is truly one of the ‘safer’ aspects – there was still a bend and movement to the ladder as I climbed up. It was just enough to give a thrill, but not too much for me to doubt the stability of the ladder. In fact, I had no room to doubt. I was supremely focused and awake. My eyes saw only the next rung, and my hand or my foot that was being placed onto that rung. I did not look up, but a few times, I did take the liberty to peek down. Down into the earth, into the icy blue heart of the Ingraham Glacier, where the edges of cracked formations made it known that this was not a place of comfort and rest. I remembered a few lines from Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar:

Brand: “That’s what I love. You know out there, we face great odds. Death. But, not evil.”

Cooper: “You don’t think nature can be evil?”

Brand: “No. Formidable, frightening. But, no, not evil. Well is a lion evil because it rips a gazelle to shreds?”

I did not want to be that gazelle.

Before I knew it, the ladder was below me and I was positioned on a nearly vertical edge of the glacier, using my ice axe, hammering the pick into the slope, like an anchor, as I pulled myself up using the guide rope with my right hand. As the slope began to mellow out and I stood upright, I didn’t even have a moment to look behind at what I just accomplished.

As we started to make our way higher up, the steeper things got. At first it was a 45 degree slope, then 50, then 55, etc. One step at a time, step, rest, step, rest, pressure breathe, step, rest, step. We utilized a few techniques on our way up, one of them being the rest step, which was, as illustrated above, stepping forward while resting, remaining on ones back leg, allowing the skeletal body a brief moment of support, then rocking forward onto your step. Then repeat, thousands of times. Another technique we used was pressure breathing. First you take a long and slow breath in grabbing as much oxygen as you can. Then, forcefully exhale, getting the air out in a near spitting motion.

Second Break – near 12,300 ft

When we got to our second break, I was feeling the altitude and the steepness take it from me. I wanted to say I was at 60%, maybe 70%. At this point we were supposed to be at 70% and then 60% at the next break, the last break before the summit where we needed 50% to get down. Augi, our rope leader looked at us and told us. “This is the only place to turn around until high break. If you continue, you have to go all the way to the next break,” which was effectively an hour away and pretty much an unknown. I felt pretty winded, legs were OK, and I felt like I was keeping things under control with very intentional breathing and very intentional rest stepping. Doug was unsure what he was going to do, I could tell even before he mentioned it at the second break, that he was starting to feel it.

At this point, it started getting colder. When we set off in the early morning, we were mostly all wearing our base layer (a sun hoodie), our technical fleece and our hard shell (a very solid rain jacket). At the second break, we pulled out our mid layer puffy jackets, took off our hard shell, and added the puffy over our tech fleeces, followed by our hard shells. Four layers of protection against the cold and brutal wind. Only our heavy parkas with 850 fill down remained in our packs which we used whenever we took a break, stood or sat stationary.

Before we set off from our second break spot, a slight amount of anxiety infected my mind. I looked at my watch to check my heart rate but it seemed to be malfunctioning, it was super low, and I knew it must have been 150 ish, way too high for what it should have been. Starting a while back, maybe 3-4 years ago, smoking weed triggered this overwhelming consciousness of my heart and its beat. I would feel it too much or the feeling of it was the centerpiece of my mind. Hell, sometimes at night, before I really knew anything about Zone heart rate regions, I would look at my then Apple Watch and see my heart at 130-140bpm, thinking I was dying or on my way. This mental connection, the feeling of what my heart was doing began to invade my thoughts way more than I wanted it to. It’s one of the main reasons I for the most part, stopped smoking weed. (I still enjoy a little puff from time to time – a few times a year maybe).

Another thing I learned about myself over the course of my training for Rainier, something that is more or less confirmed by a trait I learned about my fast tempo golf swing earlier in life, is that I have a higher than normal heart rate. I didn’t get this clinically tested, and I would like to know what’s up with my heart, but compared to my training partner Doug, I always seemed to be higher than where he was, and higher than what I thought a certain heart rate zone should be. If we were riding our bikes, aiming for zone 2, Doug would be in the 95-105 range, while I would be around 125-130 range, the peak of my Zone 2 range.

When I was setting out on this journey up Rainier, the fear of being unfit or unable layered my thoughts from time to time. Those thoughts plagued me, and the thought of not being capable enough, naturally and physically, to get up a mountain – my mountain – the one I had been training mentally for 3 years, physically maybe two years plus and emotionally most of my life, was the worst.

Would this be another failure in my life? Would it be like free diving was, where after two certification attempts, only stopped by my inability to clear the pressure in my head at 30 feet underwater and even after a trip to the ear, nose and throat doctor, who mentioned everything looked tiptop, I was still unable to get my certification in free diving? Would this haunt me like my failing, lack of a career in golf has and does? Stupidly, I held a small amount of envy and jealousy in my mind for the – what I felt was – natural abilities our guides had: being able to run or walk up rainier with ease, and do it again a day or two later.

Traversing above Gibraltar rock, threading the 50-55 degree icy sloped of the Ingraham began getting in my head. It got into my body too. The altitude was punishing, but not as bad as i thought it could have been. I continued rest stepping, trying my best to use virtually no mental energy as I hoped my body would automatically step forward as we were taught only a few days ago.

It didn’t take long for my mind to take hold of my every thought. Every step was filled with a few thoughts of doubt and fear. Thoughts like, “Will I have a heart attack here?”, or, “I should have turned around at the second break, I’m an idiot.” I felt shame, weak and disappointed that I was thinking these things to begin with. Did I train for this mental barrage of doubt and anxiety?

No. I didn’t know what to expect. I didn’t even consider I would need to be like Paul Atreides, prepared for war, for any possible attack.

When I look back, I still have no idea if I made the right decision to stop at the third break, also known as High Break located at 13,500ft. What I do know is that even at the halfway point between break two and three, I was desperate to stop and rest. It wasn’t exactly the physical pain but more of a mental anguish that attacked me. I would get into small, short bursts of calm, of being in the zone. One rest step forward, deep, full and slow inhale followed by a quick exhale, like a valve purging air. Our pressure breathing technique kept me distracted somewhat and I felt oddly happy looking ahead at Doug and Augi ahead of me, forging a slow path through a near opaque blanket of white and wind. I enjoyed the view around me, even though it felt at times like I was viewing it through a blanket of discomfort, with the weight on my back tunneling my vision.

On the way to High Break, time slowed down. The timing between breaks were about an hour and while I think we fell only a little behind pace, we didn’t seem to be too far from that pace. When I thought we might be only 15 minutes away from being able to finally rest, we might have only been 25 minutes into that stretch.

Third Break, Turning Around – 13,500 ft

As we arrived at High Break, the weather around us felt like a swirling storm of snow and wind was about to break open. I remember the level of awareness and focus on all of the guides. This was not a place to be fucking about and as Doug and myself stumbled to only flat area in the past 1000ft (or so it felt), Augi, who had been monitoring Doug asked, “Do you want to keep going up?”.

And even before Augi could finish his sentence, in the motion of sitting down on our packs, Doug, as if being asked if he wanted to be freed from a prison, said “No, I want to turn here.” We both felt the same. The mental challenge of Rainier was something I had underestimated.

But it was more than that. Doug and I had both just gotten through Covid a month prior, maybe hiked a little too much prior to our climbing days – underestimating the toll of a full snow path, whereas last year we had the luxury of light hiking boots on dirt paths – and the day before, went through a truly grueling march to Camp Muir through quite the interesting weather, punishing our bodies.

This is not exactly what we had hoped for, nor was it what we planned for. It was our real first attempt past 10,000ft and to be honest, when I also told Augi, “I’m going to turn around too”, while he was a little surprised it seemed, I felt proud, and quite relieved. Of course I was disappointed and naturally, sad and a little frustrated in myself for not being able to tough it out, but this was new territory and we’ve only been able to train in flat Florida. I would be back… but up there, feeling redlined, I wanted to head back down.

In retrospect, I know I could have suffered through the remaining 900ft of elevation, but a great unknown was if we could have then made it back down. The group just before us that were parked at High Break as well, who decided to make for the summit, they never got much of a break at the top. It was what they call a ‘touch and go’. They got to the top, “touched” it, and turned back down.

When Doug and myself both confirmed with Augi that we’d be going down – I felt guilty for not letting Augi make a Summit – he was very clear, “We can’t hang out up here too long, we need to drink water and head down as soon as possible. 5 minutes tops.”

Heading down was pure relief. After a few minutes of careful stepping, focusing on footing and ice axe placement, I felt my body start to calm down, along with my mind. Eventually, we got into a rhythm and the weather started clearing up and the sky was suddenly blue and nearly cloudless. Down-climbing a mountain goes much quicker, but at times, it can be a lot more dangerous. I was told that on the way down is where many climbers catch their crampons on their pants and trip forward into a slide.

Once we got to Gibraltar Rock, Augi again mentioned that we needed to move quickly, that the danger of rockfall here was very high. As Gibraltar Rock, which is a huge head wall on our right-side, started to tower over us, I could see why we needed to be speedy. 10-20ft long icicles attached to the cliff of the head wall would break off, pulling loose rocks on the way down. We saw a few icicles break loose high above us, high the slope and rocket down towards us.

After the icicle fall, we approached the ladder which, this time, I got to lead meaning I was the first to cross, the front of the rope. One of my favorite parts of the climb was this 10 minutes of down-climbing. I wish I had already attached my GoPro because it’s truly an experience that you can only get on a glaciated mountain. Crampons stabbing the ice, one hand holding your ice axe, picking into the side of the mountain, the sound of the steel bar on the bottom of your crampons tapping on the ladder rungs. It’s all I heard. Everything else was a million miles away.

Arriving Back at Muir and Climbing Down to Paradise

The last 30 minutes of our climb to Muir is across the Cowlitz Glacier, which we crossed earlier in the day at about 1 AM in pitch darkness. This time, we got to see what was causing a commotion on the guide’s radios. Above the Cowlitz, is a large wall of rock that tends to break free from the movement of the mountain. As the mountain warms up in the afternoon sun, more and more rocks free them selves and tumble down into the climbing path on the Cowlitz. Again, we moved quickly and everyone was vigilant, calling out, “ROCK!”, if we saw one moving toward us.

As we walked up to the Muir hut, the rest of the group who had turned back came out to meet us and congratulate us on making it to high break – even though we both felt like failures at that time. I thanked Augi for taking care of us. I knew next year I hoped he could be leading my rope again. After we took our crampons off, we set our packs down in the hut and took a load off. All in all, we had been moving for 8 hours and 39 minutes, traveling a total of 3.12 miles and burned over 2200 Calories. From Camp Muir, our watches noted that we ascended 3,332 ft, then descended the same back, naturally. We were pretty exhausted, but funny enough, I felt better at that point than the day before when we made it to Muir from Paradise.

About an hour or so after we arrived, a group of six or seven more made their return to Muir after summiting. We all went out to congratulate them, and the feeling of accomplishment in a friend came over me. I didn’t know these people outside of four days we met them on our trip, but in those few days, we learned and suffered through a very important shared experience. On our team specifically, all those that summited, lives in the Seattle area and trained specifically in Rainier National Park and surrounding National Parks.

After we all packed up our gear, ate as many calories as possible and chugged some water, we made our way for the bus down at Paradise. The long slog down the Muir Snowfield gave us plenty of time to catch up with each group member or reflect on the hours earlier. Doug and myself shared our frustrations and disappointment with our lead guide, Dustin, who, graciously, encouraged us mentioning that the conditions we climbed in today and the day before were the worst they would allow in a climb. That made me feel a little better. He told us that if it had been a clear day, he had no doubt we would have made it to the top. He gave us some training tips that made me realize there were some obvious gaps of intensity and endurance.

We glissaded, jogged and eventually made it to the main trail head of the Skyline Trail, where a little dirt path greeted us and for the first time, our boots and feet made contact with the hard ground. On the first foot plant, I felt my toes bang against the front of my foot – they were already swollen from the nearly 10,000ft of elevation we covered on that day. My knees pounded at the joints and I started to drool over the idea of sitting on that bus back to the RMI base camp with regular sneakers on my feet.

Finally, the end of the trail peeked through the trees ahead, my feet and knees burned with pain but I focused on the next step, the next set of trees. We boarded the bus, tossed our packs in the back trailer and I slid my shoes on. Relief. While my mountaineering boots were incredibly comfortable and I never felt any sense of coldness, I was happy to peel them off of my damp, warm feet.

We drove the 45 minutes back through Rainier National Park to Ashford where the RMI base camp/headquarters is and I felt a wash of emotions and thoughts. I was mostly exhausted, too much so to really put much real thought into anything, but, I knew I felt a strong accomplishment in having just completed a massive adventure, something that I had focused so much mental and physical energy into. My disappointment in not summiting was easier to digest when I looked back up at the towering volcano and realized that on my own, training primarily in Florida, I made it up to just 900ft away from the top of what felt like many miles away from where I sat in that bus. That too, was not just a feeling, but my reality.

July 4th – 7th.